Therukoothu performance. Photograph by Esplanade.

Historians may locate the earliest sign of modern Tamil settlement in Singapore in the 1827 establishment of Sri Mariamman Temple for such a feat is premised on a sense of community driving collective action in raising capital and labour resources as well as support from the colonial state. As a community site where the Tamil people could gather for extended periods, Sri Mariamman Temple provided the first platform for Tamil Theatre in Singapore as traveling drama troupes—Nadaga Sabhas—from India set up stage in its large grounds. Performances took multiple forms such as Therukoothu (street theatre), Kathakalatchebam and Villupattu (both styles of lyrical storytelling). Besides entertainment, these performances were a key medium for the instruction of cultural values as well as for broadcasting social and political messages to a community far from ‘home’. Theatre, as a medium, could gather and unite a wide spectrum of Tamil society, from layman labourer to merchant and scholar. Tamil theatre in Singapore has since moved out of temple grounds, but the same confluence of capital, labour, and support that saw the earliest temple built similarly underscores the development of a Tamil Theatre in Singapore into a Singaporean Theatre in Tamil.

The 1930s herald a distinct demographic shift in the Tamil community in Singapore. Far more women and families have now traveled to and taken up residence in Singapore, a key indicator of longer term settlement. Tamil individuals and families exhibit a greater sense of fidelity to the local context, expanding beyond concern for kinsmen to affiliation with the wider Tamil community living in Singapore. The Tamil theatre enthusiasts amongst them, including some previously from the traveling drama groups, found in theatre a platform to explore their interest with like-minded peers, perform the Tamil culture, and voice opinions on life in colonial Singapore.

In this time of profuse short-term and circulatory migration, theatre enthusiasts such as Amuthar Thambiya Pillai, Madhavanel Pillai, and Na. Palanivelu chose to settle in Singapore and continue staging plays. Madhanavel Pillai formed the theatre group, Devi Ghana Sabha, and staged presentations of the Hindu Puranas such as with Valli Thirumanam (1937) and Bama Vijayam (1938), as well as the Tamil epics such as with Kovalan (1937) (an adaptation of Silapathikaram), all in Alexandra Hall. Now staged outside the temple space, theatre remained a vehicle for propagating culture and moral messaging to the Tamil community in Singapore.

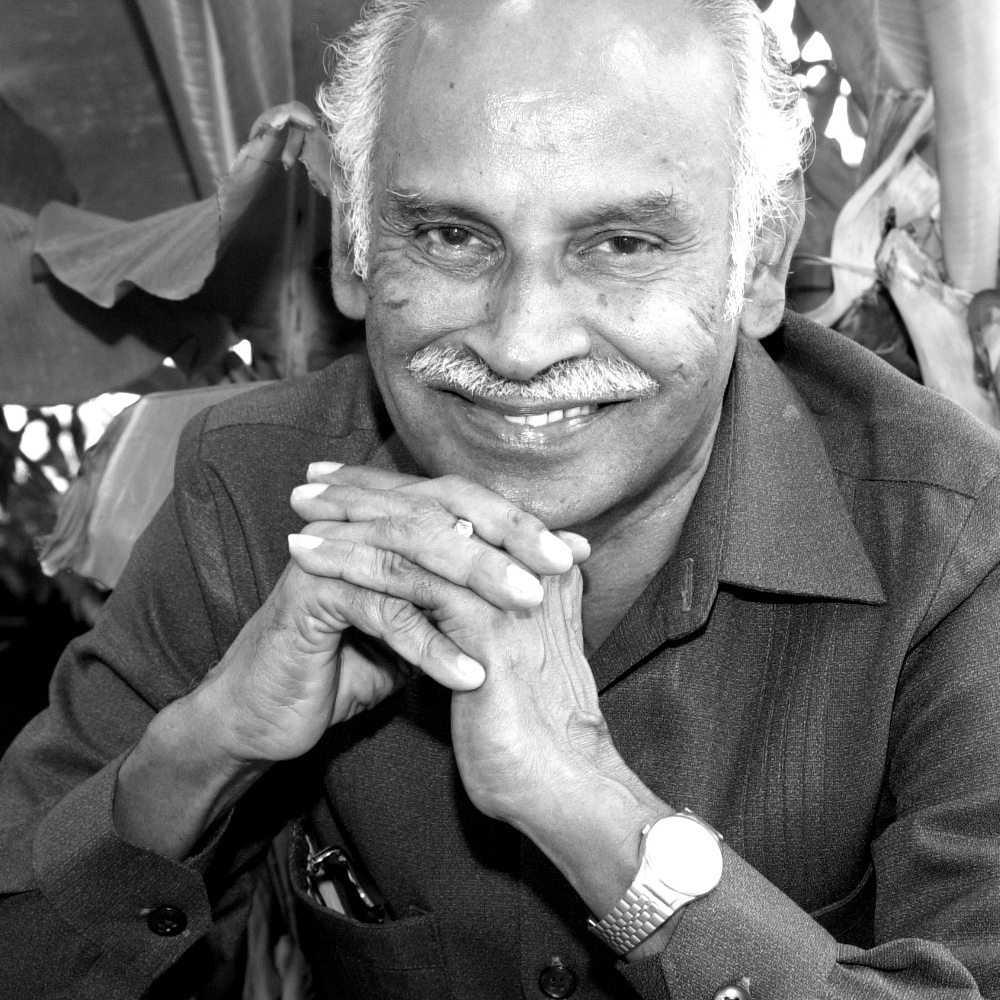

Ko Sarangabani. Screenshot from TRIBUTE TO TAMIZHAVEL KO SARANGABANI (Youtube Video)

This period of Tamil history is particularly marked by the ascendance of the Tamil Reform Association (TRA). Established in 1930 by Ko. Sarangapani (also Tamil Murasu’s founding editor), TRA is the local proponent of the formindable Self Respect Movement that had began in Tamil Nadu in 1925. The use of Therukoothu was pivotal in TRA’s efforts to propagate its messages of social reform—including the eradication of caste discrimination, alcoholism, gender violence, and the promotion of Tamil pride, culture, and literacy. Examples include Suguna Sundaram (1936) and Gauri Shanker (1937) that, respectively, denounced caste discrimination and promoted widow re-marriage. These were penned by Na. Palanivelu and staged in Alexandra Hall.

The field however remained predominately an ametuer one as enthusiasts took on the tasks of writing, rehearsing, and staging, and costs were covered out of pocket. Theatre remained an important platform for the Tamil community’s social and political discourse, even as other media flourished. Thus in this period where sojourn starts to give way to greater settlement, Tamil theatre served as a carrier of Tamil culture and politics between Tamil Nadu and Singapore, ennobling the Tamils in Singapore with a socially progressive community and stronger political consciousness, setting the tone for this emerging Tamil diaspora and its theatre.

The onset of WWII predictably brought community-led cultural productions to a halt. This disruption continued amidst the sociopolitical upheaval in a community and nation negotiating the uncertainties over migration and citizenship rights heralded by India’s Independence, Home Rule in Singapore, Merger with Malaya, and Singapore’s Independence.

Yet, this lull in Tamil theatre in Singapore continued in the immediate post-Independence period, reflecting the financial and social concerns of a field of ametuer theatre practitioners. Part-time artistes were hesitant to rely on theatre, and young artistes moving into adulthood and with family commitments prevented them from performing on stage regularly. Theatre as a profession was socially unattractive as Tamil society at large regarded actors with contempt. While this attitude severely curtailed the recruitment of new talent, a few women begun venturing into the field in this time, though they were mostly relatives of established male artistes.

Even when performances were staged, ticket sales were hard to make as the small audience pool preferred to spend their money at the new, more alluring cinemas. A few theatrical performances were staged in this period nonetheless, but they were primarily billed as the main part of a variety cultural show staged in community centres and school halls, or in the New World and Great World entertainment parks. While a few new Tamil theatre groups emerged in this period, without the patronage patterns of before and with the difficulty in retaining artistes, many more groups folded.

S Varathan. Photo from Esplanade Offstage.

The 1970s saw a resurgence of interest and talent in Tamil theatre, arguably grounded in the 1971 inception of the Inthia Kalaignar Sangam (Singapore Indian Artists’ Association, SIAA). S. Varathan and his group of Tamil stage and television stalwarts formed SIAA with the expressed purpose of gathering Tamil drama artistes in order to boost a dormant field. Within the single decade, they succeeded in attracting crowds, funding, and new talent. Significantly, several of their productions written by S. Varathan explored the local context and tensions of Singaporean Tamil lives. Alongside other productions that engaged with the classic stories from Tamil and Hindu epics, this diversity attracted new audiences and large crowds to the theatre. Theatre once again played the role of community-making, as evident in the way productions were frequently fund raising avenues for donations to hospitals, a new building for SIAA, and even the construction of a new Hindu temple in Jurong East.

Through its productions, joint programmes, and even children’s classes, SIAA provided a platform for musicians, singers and dancers too. Concurrently, skits had become a norm in staged variety shows, on television, and radio, thereby expanding opportunities for existing artistes and attracting new interest in playwriting and acting. SIAA and several other Tamil theatre productions also availed of grand new professional venues like Victoria Theatre and the National Theatre, elevating, in the eyes of some, Tamil theatre from ‘the streets’. With changing attitudes to the entertainment professions and in seeing the theatre form as Art, Tamil theatre in this period quickly attracted new talent, including women actors and playwrights. Several other groups also added to the renewed energy in a field now confidently claiming a place in Singapore Theatre—Inthia Kalai Mandram (Indian Arts Association), spearheaded by playwright and director S. S. Sarma, focused on comedies and moral plays; and Vennilaa Kalai Arangam (Vennilaa Arts Theatre), and the Tamil Youth Club of Singapore Tamil Peravai (Tamils’ Representative Council) sporadically staged plays that offered young Singaporean Tamils more opportunities to explore theatre.

The success of the previous decade inspired a mushrooming of new Tamil theatre groups in the 1980s and early 1990s. This next generation broke step with past patterns, now armed with new literary interests, postmodern themes, and greater funding opportunities. Groups such as Agni Koothu, Ravindran Drama Group (RDG), Supradeepam, and Auvaiyar Nadaga Kuzhu focused on themes that reflected the lives of their Singaporean Tamil audience, expanding theatre from a site for the instruction of Tamil sociopolitical values to a site for critically examining Tamil society. For instance, Kudumbathin Alaigal (Family Waves, 1988) and Madamaigal Maatrapaduma (Can Stupidity be Changed?, 1989) by G Ravindran (after whom RDG is named) and staged at The Substation, both highlight the idiosyncrasies and trials of the average Singaporean Tamil family. Such expositions are not without pushback as seen in the objection to and subsequent stay on the English staging of Talaq (Divorce)—about the marital life of an Indian Muslim woman—after successful Tamil stagings in 1998 and 1999 by Agnikoothu.

Led now by artistes educated in English language literature and its approach to theatre, Tamil Theatre from the late 1990s played freely with classic English and Shakespearean plays, adapting them into Tamil. Examples include Macbeth (2000, 2001) by RDG; Thondan (2008), Mirror Theatre’s adaptation of Titus Andronicus; Vanthavan Yaar (2004) RDG’s adaptation of An Inspector Calls by J.B. Priestley; and Avant Theatre’s 12 A M (2012), an adaptation of Reginald Rose’s 12 Angry Men. The Hindu and Tamil epics nonetheless remained evergreen throughout the decades, though new thematic interests and positionalities as cosmopolitan Singaporeans also informed the deconstructions of these epics in the new century. Hemang Yadav’s Maya: Demon Architect (2014) is an example.

Further breaking with the previous emphasis on classical or at least formal Tamil, these companies increasingly played with Singaporean colloquial speech patterns and bilingual plays to reach non-Tamil speaking audiences. Shanmugam: The Kalinga Trilogy by Mirror Theatre is a key example of a bilingual staging with the expressed intention of sharing a Singaporean Tamil narrative with the non-Tamil speaking Singaporean theatre audience—a clear demonstration that this field sees itself as part of Singapore Theatre at large. Similarly, since 2013, RDG has been organising Pathey Nimidam, a theatre festival for short form plays, in which non-Tamil groups also participate to stage Tamil plays. Expanded financial capacities in this period is no doubt key to the proliferation of groups and productions in these decades. Between available funds from the community’s socioeconomic progress and expanded funding sources and quantums from state and private institutions, Tamil theatre productions are able to explore more complex multi-day stagings and increase the frequency of new productions. This crucially translates into the greater viability of Tamil theatre as a career, keeping talent in the field.

As with other segments of Singapore Theatre, formal theatre training has translated to greater professionalisation in all aspects of Tamil theatre. This includes working with trained technical designers and crew, as well as producers and arts managers. This period has also seen great leaps in bringing Singaporean Tamil theatre into schools. In 2014, S.V. Shanmugan’s Kudumbam (Family) and T.T. Dhavamanni’s Kadhal Enna Vilai (What is the Price of love?) were added to the A-Level Tamil Literature syllabus. Several more local plays have since been included, including S. Varathan’s Singapur Maapillai (Singapore Groom) first staged by SIAA in 1985.

Singaporean Theatre in Tamil has also now expanded beyond Tamil. First with the inclusion of surtitles, and later with bilingual or even English-language productions, some production companies and artistes position themselves as Singaporean theare practitioners, who may specialise in Tamil languages and narratives. On the surface Tamil theatre may seem ‘stuck’ on restaging the same old stories from the Tamil and Hindu epics, yet these ought to be understood as the evergreen foundations of a Tamil literary tradition and cultural world. Such familiar narratives have also inspired bold new experiments in digital technology. In 2021, Agam Theatre Lab launched Duryodhanan, Singapore's first augmented and virtual reality (AR and VR) Tamil-English theatre production.

Where Tamil theatre had first served as a public medium for political and social messaging for a newly settling community, this now maturing field is turning to active introspection in asking what roles it ought to play for an evolving Singapore Tamil diaspora. The conversations raised at theatre forums, such as Nadagavathi by Agam Theater Lab, clearly demonstrate that this is a multivocal field with many possible directions for exploration and growth, as Singaporean Theatre in Tamil and beyond.

Tamil Theatre in Singapore first set stage where the Tamil community gathered, it now seeks to serve as a site where the Singaporean Tamil community may be gathered to see, question, and celebrate itself. The shifting constellation of capital, labour, and public support over the decades has shaped how the field fared. Ultimately professionalisation of theatre companies and practitioners helped accrue and manage funding as the Tamil community, state, and theatre scene at large supported the development of a Singaporean Theatre in Tamil as it stepped out, up, and beyond.

The Digital Archive of Tamil Theatre, by National Library Board and Tamil Digital Heritage Group

Nallu Dhinakaran. Performance as a Carrier of Tamil Culture in Singapore. Unpublished Bachelor’s Thesis. Singapore: National University of Singapore, 2012

Published: 23 March 2022